Moving away from Gradient Descent

Training a neural network is arguably the most complex procedure in the entire pipeline of solving a machine learning problem. It is also the most important part. Modern networks need several GPUs and days or even weeks to train. It is crucial then, to use the right algorithm.

The problem of training a neural network essentially boils down to an optimization problem. However, there are slight differences to note between a pure optimization problem and one in the context of machine learning. In a pure optimization problem, our main goal is to minimize some function $J$. In ML however, we care for some metric of performance $P$ on a test set. We improve $P$ indirectly by reducing a different cost function, $J$. What this means is that we may not actually desire reaching the global minimum of the cost function, if it doesn’t translate into good performance on the test set.

Our cost function can be defined as [ J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{(x, y) \sim \hat{p}_{data} } L( f(x, \theta), y ) ] where,

- $J$ is the cost function

- (x,y) is the input and target output respectively

- $f(x, \theta)$ is the predicted output

- $L$ is the per-example loss function

- $\hat{p}_{data}$ is the empirical distribution, or the distribution of the training set

- $\mathbb{E}$ is the expectation over the data distribution

Gradient Descent

The Gradient Descent algorithm is a greedy algorithm which seeks a local minimum of a given function. It has established itself as the de facto standard in training machine learning models. It is known to work well and is not especially computationally expensive. Stochastic gradient descent in particular has strong theoretical guarantees of saddle point avoidance and improved generalization.

Consider the cost function $J(\theta)$ that we wish to minimize. Note that for any optimization problem on a function, the output must be a scalar for the minimization to make sense. Here, we are consistent with this requirement as any expectation value is always a scalar.

The gradient descent works by making use of the gradient of the function. The gradient represents the slope of the function. More specifically, it points to the direction of the greatest rate of increase of the function, and its magnitude gives the slope in that direction. Gradient descent advocates that we move the opposite direction, or down the steepest slope, in our search for the minimum. This can be expressed as: [ \theta := \theta - \alpha \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) ] where $\alpha$ is the learning rate. Several iterations of the above update procedure are required before $\theta$ begins to approach the minimum. Note that if $\nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) = 0$, then no further updation can be made. Training a neural network then is simply computing the above values, executing the update, and repeating until $\nabla_{\theta} J(\theta)$ approaches $0$.

Observe that gradient descent makes no guarantees that it reaches the global minimum after its execution. However, in the problem of neural network training, we are not persistently keen on finding a global minimum. Indeed, such a one could even lead to overfitting. What we are interested is in the generalizability achieved, or how good the performance will be when subjected to a different dataset. For this, researchers now conclude that perhaps a global minimum is not necessary, a sufficiently low-cost local minimum would do just fine.

But does GD guarantee that it can serve us a local minimum at least? The answer unfortunately is no. We could get stuck at a saddle point too. However, empirically it is has been shown that, while progress becomes extremely slow near a saddle point, the gradient descent procedure does somehow manage to eventually evade it. Of course this is only as long as it doesn’t exactly land on a saddle point. The likelihood of that is low (but still present!).

Thus it seems that gradient descent seems to generally work irrespective of any problem! Well, almost but not quite. A major challenge that gradient descent does face is the problem of ill conditioning. Before delving into that, let’s take a step back and understand the related concept of Hessian matrix, and some of its applications.

Hessian matrix

First, we define the Jacobian of a function, $\boldsymbol{J}$. Formally, if we have a function $\boldsymbol{f} : \mathbb{R}^m \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n$, then $\boldsymbol{J} \in \mathbb{R}^m \times \mathbb{R}^n$ such that $\boldsymbol{J}_i = \frac{\partial}{\partial x_i} \boldsymbol{f}$, or $J_{i,j} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x_i} f_j $, where $ 1 \le i \le m, 1 \le j \le n $. In simpler terms, the Jacobian is simply a matrix containing all the first order partial derivatives of the function. Observe that for our cost function, the Jacobian is simply a vector.

In a similar vein, the Hessian matrix, denoted by $\boldsymbol{H}$ contains all the second order derivatives of a given function. Suppose we have $f : \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, then $\boldsymbol{H}_{i,j} = \frac{ \partial^2 }{ \partial x_i \partial x_j } f$. Thus, it can be said that the Hessian is the Jacobian of gradient.

Note that whenever the second order partial derivatives are continuous, we have [ \frac{ \partial^2 }{ \partial x_i \partial x_j } f = \frac{ \partial^2 }{ \partial x_j \partial x_i } f ] Thus, $\boldsymbol{H}$ is symmetric and hence, we can perform eigendecomposition on $\boldsymbol{H}$ and obtain real eigenvalues.

Second order derivative test

Let’s recall the second order derivative test in 1 dimension, for a function $f$ at a critical point, i.e. $f\prime (x) = 0$.

- $f \prime \prime (x) > 0$ then $x$ is a point of local minimum.

- $f \prime \prime (x) < 0$ then $x$ is a point of local maximum.

- $f \prime \prime (x) = 0$ then the test is inconclusive as the point may be a saddle point or a part of a flat region.

The second order derivative test in higher dimensions is slightly more powerful. These are done by looking at the eigenvalues $\lambda$, of $\boldsymbol{H}$.

- All $\lambda > 0$ then $\boldsymbol{H}$ is positive definite and the point is a local minimum.

- All $\lambda < 0$ then $\boldsymbol{H}$ is negative definite and the point is a local maximum.

- At least one $\lambda > 0$ and another $\lambda < 0$, then the point is a saddle point.

- All non-zero $\lambda$ are of the same sign, and there’s at least one $\lambda = 0$, then the test remains inconclusive.

Using the Hessian to evaluate Gradient Descent

This is one of the areas where Hessian’s importance shines. As we know, in each iteration gradient descent chooses some direction, and based on our learning rate or step size, we move that much distance in said direction. We know empirically that gradient descent usually reaches local minima. However, as a computer science student, one is naturally obsessed about the efficiency of any approach too. But how do we evaluate the path that gradient descent takes to get there? For example, suppose there was a short but wide hill. GD would insist on a long path around the hill when instead we could have just climbed the hill and reached minima far more efficiently. Note that the problem of realising efficient paths is highly complex and under active research, and we are still far from realising them. What we can do now however, is check how good a step GD decides to take in any particular iteration. That’s where the Hessian comes in.

Consider the second order Taylor approximation around the point $a$.

[ f(x) \approx f(a) + (x - a)^T \boldsymbol{g} + \frac{1}{2}(x - a)^T \boldsymbol{H} (x - a) ] where $\boldsymbol{g}$ is the gradient of $f$.

Now, suppose we carried out one step of the gradient descent algorithm. Let the learning rate be $\alpha$. Then the updation step would result in a new point $x = a - \alpha \boldsymbol{g}$. Substituting this value, we get [ f( a - \alpha \boldsymbol{g} ) \approx f(a) - \alpha \boldsymbol{g}^T \boldsymbol{g} + \frac{1}{2} \alpha^2 \boldsymbol{g}^T \boldsymbol{H} \boldsymbol{g} ] This is an important result as it gives us a useful tool to monitor how well an update gradient descent executes in each iteration. Note that ideally we want $f(a - \alpha \boldsymbol{g}) < f(a)$. But, if $\boldsymbol{g}^T \boldsymbol{H} \boldsymbol{g}$ is large enough, then gradient descent would take a step going uphill!

Can that really happen though? Can GD actually take a step going uphill? It certainly can, a scenario especially likely when the condition number is high.

Condition number of a Hessian matrix

The condition number of any matrix measures how much the second derivatives differ from one another. For positive symmetric matrices like the Hessian, the condition number simplifies to [ c = \frac{\max_i \lambda }{ \min_i \lambda} ] where $\lambda_i$ are the eigenvalues of $\boldsymbol{H}$.

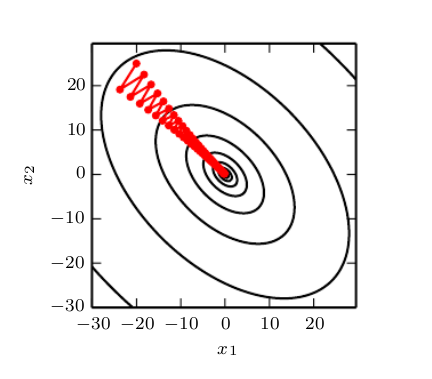

When $c$ is small, the contour of the function remains circular. The problem of ill conditioning occurs when $c$ is large. The contour becomes ellipsoid in this scenario, and gradient descent takes many unnecessary steps.

A large $c$ implies that the second derivatives are very volatile with respect to one another. Thus, in one direction, the derivative increases rapidly, while in another direction, slowly. We recollect that gradient descent is greedy; it always chooses the path of steepest descent. GD has no knowledge if this path will yield the minimum. If the path to the minimum actually requires an update along the direction of lesser slope extremity, then GD is prone to missing it.

The following analogy will make this clear. Imagine a canyon along the slope of a mountain such that you are standing somewhere on the canyon wall. The river within has the same slope as the mountain. To reach the valley, we need only to walk along the river. However, GD searches for the steepest slope. The walls of the canyon have much steeper slopes than the mountainside. So GD in its greedy endeavor, scales the canyon wall instead of going in the direction of the river. If step size is large, then GD will overshoot the river and climb the opposite canyon wall. While our objective is to reach the bottom, GD will waste time scaling the canyon walls like this. If step size is small, or allowed to decay, we need many more iterations to reach the bottom.

Image credits: Deep Learning, Goodfellow et.al., pp91

is only present at one point. Image credits.

Why is GD unable to handle this? It’s simply because gradient descent relies on too less information to perform the update. You can think of gradient descent as a myopic man (without glasses) who takes a small step depending on what he is able to discern in his immediate surroundings.

In our quest for efficient paths, what we need is not a myopic man, but one who can look at the entire big picture clearly. That man is Newton! To be more specific, his brainchild - the Newton’s method.

Newton’s method

The efficiency of the Newton’s method lies in the fact that it utilizes the information contained in the Hessian matrix.

Consider the second order Taylor approximation again around the point $a$, [ f(x) \approx f(a) + (x - a)^T \nabla_x f(a) + \frac{1}{2}(x - a)^T \boldsymbol{H} (x - a) ] Solving for a critical point $x^\prime$, \begin{align*} \nabla_x f(x^\prime) &\approx \nabla_x f(a) + \nabla_x \{ (x^\prime - a)^T \nabla_x f(a) \}+ \nabla_x \{\frac{1}{2}(x^\prime - a)^T \boldsymbol{H} (x^\prime - a) \} \newline 0 &\approx 0 + \{\nabla_x f(a)\}^T + \frac{1}{2} \times 2 \boldsymbol{H} \times (x^\prime - a) \newline 0 &\approx \nabla_x f(a) + \boldsymbol{H} \times (x^\prime - a) \end{align*} Pre-multiplying both sides by $\boldsymbol{H}^{-1}$, \begin{align*} 0 &= \boldsymbol{H}^{-1} \nabla_x f(a) + (x^\prime - a) \newline x^\prime &= a - \boldsymbol{H}^{-1} \nabla_x f(a) \end{align*}

When $f$ is a positive definite quadratic function, Newton’s method jumps to the minimum of the function directly. If $f$ can be locally approximated as quadratic, only a few iterations are required.

Optimization algorithms can then be classified as first order optimization algorithms, or second order, depending on the derivative they utilize. Observe the similarity between the gradient descent, a first order optimization algorithm, and Newton’s method, a second order optimization algorithm : \begin{align*} \theta &:= \theta - \alpha \nabla_{\theta} J (\theta) \newline \theta &:= \theta - \alpha \boldsymbol{H}^{-1} \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) \end{align*} The first depicts the equation of gradient descent, and the second that of Newton’s method. Note that both methods are equivalent if $\boldsymbol{H} = \mathbb{I}$, the identity matrix. Thus, gradient descent implicitly assumes that the problem is well conditioned since the Hessian equals the identity matrix. Whenever this assumption fails, gradient descent fares poorly.

Thus, there are two chief advantages of the Newton’s method. One, the speed of convergence is much faster since only a few iterations are required. Two, it forms no assumption on the conditioning of the problem, and is hence more robust.

So if Newton’s method is so awesome, why is it not used more commonly?

Because it’s not perfect. The first disadvantage is that Newton’s method is attracted to saddle points as well, since it explicitly solves for a critical point. Gradient descent on the other hand, is designed to move downhill and is not explicitly solved for a critical point. It has also empirically been observed that gradient descent can manage to escape a saddle point. The proliferation of saddle points in high dimensional spaces makes this a serious concern for Newton’s method.

The second disadvantage is in the computation involved. Performing one step of Newton’s method is highly computationally expensive. Calculating the Hessian matrix takes $O(n^2)$ time, and calculating the inverse $\boldsymbol{H^{-1}}$ takes $O(n^3)$. Each step of gradient descent on the other hand, is significantly cheaper standing at just $O(n)$.

So what is the solution?

Neither method in its vanilla state is the best solution. Newton’s method has many derivatives aimed at addressing the issues it faces. BFGS algorithm attempts to ease the computation burden by estimating the inverse Hessian without directly computing it. L-BFGS is an even more efficient version which reduces the memory footprint of BFGS. Saddle-free Newton’s method directly addresses the problem of being attracted to saddle points. However, all these promising methods still remain to be tested for scalability and as such have reclused as a topic of research for now.

Gradient descent, on the other hand, has a popular derivative that specifically addresses the ill-conditioning problem: momentum. Momentum draws an analogy with a physical force like gravity. It maximizes movement towards the minimum while suppressing oscillations. A thoroughly detailed explanation (with beautiful interactive visualizations) can be found here.

Thus, for now we still are stuck with gradient descent. Future research though can open gateways to more sophisticated algorithms which will release some of the load on our hardworking GPUs.